For one week in the Fall of 2005 (twenty years ago!), I served as “guest editor” for what was then one of the preeminent websites for comicbook-related news, Newsarama. Over the course of that week, I conducted a few interviews with fellow comicbook professionals, one of which I’m reprinting below (with a few minor edits). My effusive car waxing aside, this is a pretty good talk with a pretty great comicbook writer…

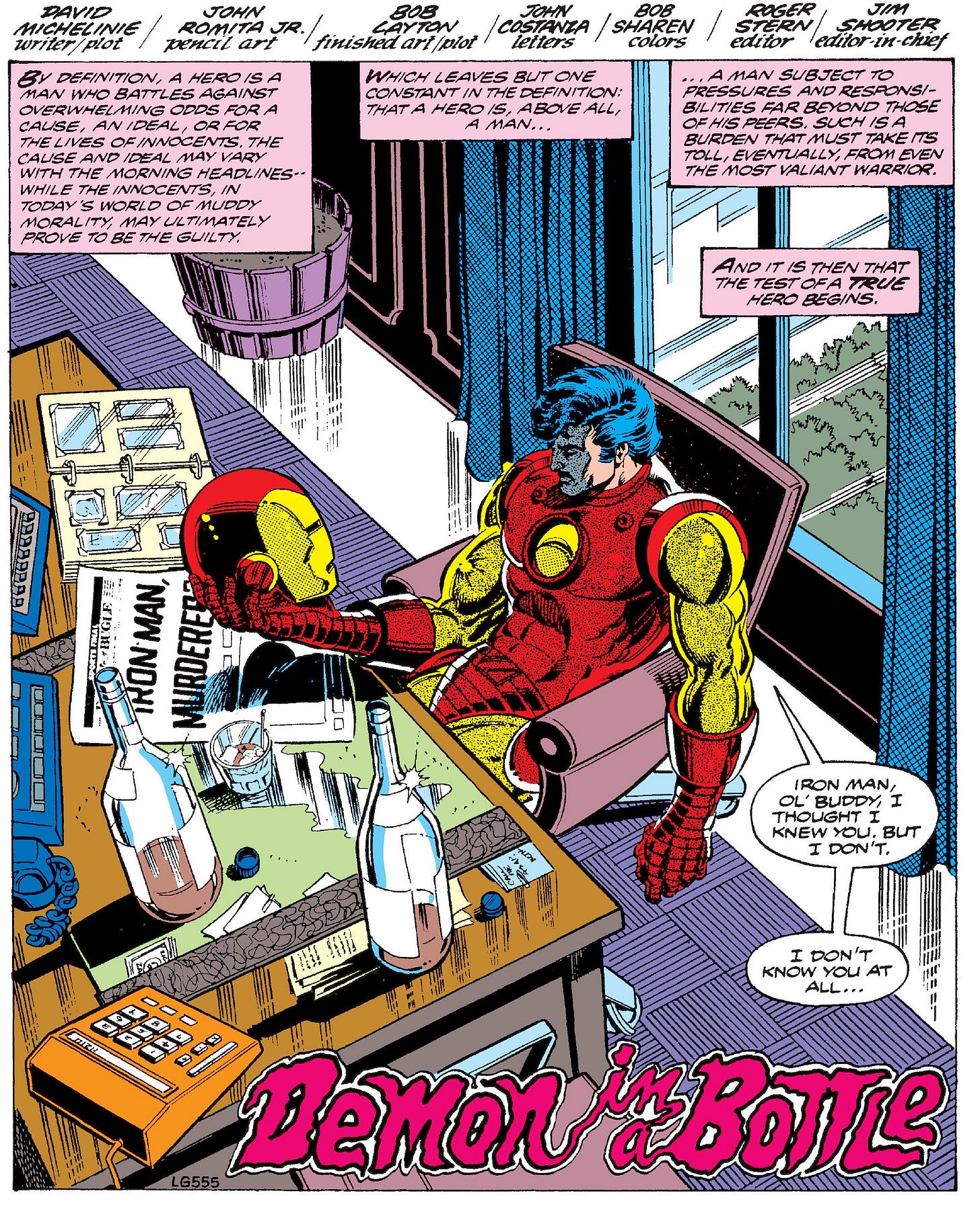

“Business is a tough world these days. It makes a man hard.”

-- Tony Stark, IRON MAN #123

Does dialogue get any better than that? David Michelinie was my first “favorite writer”. In fact, he was my favorite writer before I was old enough to know I had a favorite writer! His work on IRON MAN and especially THE AVENGERS were seminal, early influences on my own work. His stint on AMAZING SPIDER-MAN with artists Todd McFarlane and Erik Larsen was one of Marvel’s top sellers for years. His body of work includes SWAMP THING, CAPTAIN FEAR, WEB OF SPIDER-MAN, THE BOZZ CHRONICLES, STAR WARS, H.A.R.D. CORPS and ACTION COMICS. More than being a great writer, David is truly a class act, and words can’t really express how honored I am to have been able to interview him about his career and his craft. This is what it’s all about, folks…

JOE CASEY: Okay, David, I’ve always thought you were a rare breed of comicbook writer, the kind I think we could really use more of these days. Your work always seemed to aspire to entertain and engage without the accompanying bluster that modern creators tend to spew about how they’re going to reinvent the wheel (and I fully admit, I’d count myself as occasionally guilty in that regard). As a fan, I never saw you take a job and then enact change for the sake of change. You simply settled in and told great stories, as opposed to being overly concerned with “making your mark”. So, now that I’ve got you here and can just ask you flat out… when you’d approach a new writing assignment, whether it was UNKNOWN SOLDIER or THE AVENGERS or SPIDER-MAN or SUPERMAN, what tended to be your thinking? Did you have some personal statement of intent with each new series you took on, or was it simply just to tell good stories?

DAVID MICHELINIE: Well, you pretty much hit the nail on the head when you used the word, “entertain.” I’m not a terribly deep thinker, and I’ve never really had any interest in revealing Great Truths or imparting my hard-earned but spotty wisdom to others. I’ve always loved to read, both comics and prose, but mostly as a form of entertainment. And offering entertainment is all I’ve really sought to do with my writing. If someone spends twenty or thirty minutes reading one of my stories, ends up with a smile on their face or a lump in their throat, and then just goes on with their life, I’m perfectly happy with that.

As for making changes, I usually let respect and logic be my guides there. For example: when I took over IRON MAN for my second run on that book, the series had developed characters and situations that weren’t the type I was particularly interested in pursuing. But I felt that the previous writer, and the readers who had enjoyed his work, deserved more than having everything suddenly and jarringly go in a different direction. So my co-plotter, Bob Layton, and I constructed a two-part story that tied up loose ends in a way that we hoped would be satisfying to the readers, while at the same time providing a believable turn towards the direction we wanted to go with future stories. Further example: when I took over THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER, the title character impersonated people by wearing full-head masks. I found it difficult to believe that such masks would fool anyone, especially friends and relatives, so I altered the process to have the Soldier use facial appliances and character-specific make-up, like a Hollywood special effects expert. That wasn’t change for the sake of change, but because it simply made more sense to me.

CASEY: I know a little bit about your career biography. You’re one of those guys that took an incredible leap of faith and moved to New York and showed up on DC’s doorstep, looking for work after what I’d consider the most bare bones encouragement from Michael Fleisher, who was Joe Orlando’s assistant at the time. Maybe I’m misrepresenting it, but when you look back on your first “break”, what kind of perspective do you have on it…?

MICHELINIE: I’m stunned that I ever did such a thing. People who know me consider me to be conservative and overly cautious, and they’re generally right. But though I’m not a particularly ambitious or aggressive person, I do tend to recognize opportunities and make the most of them. When I first moved to New York I had six hundred dollars from my savings account, and another five hundred my mom gave me. I lived on canned spaghetti and tap water for ten months, learning my craft and selling occasional six-page stories (at ten dollars a page!) to the likes of HOUSE OF MYSTERY before I got my first shot at a series job. But I knew I’d gotten a toe in a very special door, and if I didn’t push my way through at that time the door might never open again. These days I look back at that time and wonder, what the hell was I thinking?!?

CASEY: Well, I’m damn glad you pushed. Obviously, I’m a HUGE fan of your work. I’ve read tons of comicbooks you’ve written, at just about every company you’ve worked at, and I’ve always been impressed at how at home you are with the language of comicbooks. Your stories tend to read so effortlessly. Especially since I’m assuming you’ve written most of your work plot-first, it’s even more impressive. Was writing comicbooks something that always came easily to you, or do you feel like you worked hard at your craft?

MICHELINIE: Writing comics was very difficult for me to learn, and I didn’t start feeling comfortable with it until I’d been making a living at it for a couple of years. And didn’t really feel confident in my abilities for another year or so after that. Most people outside the field don’t realize how limiting, how specific, comic book writing is. With a novel, short story or screenplay, you write until the story is done, whatever length works. With comics, each story has to fit into a specific page length--no more, no less. You also have to be concerned with the number of panels and number of words you use. Call for too many panels, the art grows tiny and looks like postage stamps; use too many words and the work starts looking like a textbook with spot illustrations. It takes quite a bit of discipline.

I remember a cartoon from an old EC comic: it showed an artist leaning against a door jamb, drawing table in the background, with sweat pouring down his face. The caption was something like, “Whew! Drew a whole panel today!” I think it was meant as a joke about an artist who was rather leisurely in his work habits, but I could really identify with that guy. There were days early on when I’d struggle over every word, second- and third-guessing everything about it. Some days I’d literally get only a single panel written before I’d give up and spend the rest of the day wandering around Queens, feeling like a failure. But eventually the effort, thought and desperation paid off, and the writing process smoothed out as I actually learned how to put stories together.

As for using the language of comic books to make my stories read effortlessly (and thank you so much for saying so), whatever ability I may have in that regard was brought out by my mentors, Michael Fleisher and Joe Orlando. Michael taught me the most important thing I’ve ever learned as a writer: “Never assume that the reader knows what’s in your mind.” That sounds so simple, so basic, but there are still a lot of writers who don’t get it. They’ll be familiar with the backgrounds and nuances of the characters and situations in a particular story (especially if it’s part of a multi-story arc) and so will write that story as if everyone else knows exactly what they know. But every single story is going to be read by people who are coming to it for the first time, and they’re likely to become confused, or totally lost, if you forget to tell them what’s going on. You don’t want to write down to your audience, and there’s a thin line between being clear and being condescending. But if you can learn to walk that line, I guarantee you’ll be a better writer.

CASEY: All too true. Now, as far as I’m concerned, and with all apologies to Stan, you were THE MAN at Marvel right when I was really connecting with comicbooks on a serious level for the first time in my life. You were a literal double-threat with THE AVENGERS and IRON MAN, work that still holds up to this day. When you look back on that specific period of your career -- if, in fact, you ever do -- what’s your take on it now…?

MICHELINIE: It was wonderful, probably the overall happiest time I’ve spent as a writer. I left DC Comics after two incidents in which I was screwed over because they wanted to appease an artist, at the expense of my scripts. I called Jim Shooter at Marvel and asked if I could get work there. He answered, quote -- “Is today too soon?” -- unquote, and immediately sent me 22 pages of an Avengers story to script. When I got to Marvel it was like going home, even though I’d never been there before. The administration at that time was very much dedicated to telling stories, and they had a genuine respect for writers.

And incidentally, speaking of THE MAN, that was also the period when I first met Stan Lee. Other than meeting Stephen King a few years later, that was the only time I’ve ever been reduced to the state of Gushing Fanboy. And I loved it.

CASEY: I know exactly how you feel. One thing that completely blows me away about your work on THE AVENGERS is that you weren’t a fan, you came into it completely cold when Jim Shooter handed you the gig. How did you go about finding your voice on that book and how’d you do it so quickly? For my money, your writing was completely assured on that series right from the get-go…

MICHELINIE: Wow, thanks. In all honesty, there were two factors involved in my quickly learning to write THE AVENGERS: Jim Shooter, and crap-your-pants terror. As you say, I had never read THE AVENGERS before. I’d been a big Marvel fan but, other than Spider-Man, I’d mostly been drawn to second-tier characters like Sub-Mariner, Silver Surfer, Conan and the like. The first few issues of AVENGERS that I scripted were from Shooter plots, and were part of a long arc called The Korvac Saga. So I read and absorbed the already-written stories in that arc, and then sat down with Jim each time a new story had been drawn. He’d go over the plot with me page-by-page, explaining character traits, motivations, relationships, everything. It was an intense learning period, but I basically just tried to follow what Jim had already thought out, and to emulate his speech patterns for the characters. It was a really solid foundation and I was highly motivated since I wanted to keep writing for Marvel. Of course, having a great artist like George Perez draw the book when I finally took over the plotting myself made it easier, too.

CASEY: This is something I’ve always wanted to ask you… what were the circumstances of you and Bob Layton returning to IRON MAN in the 80’s. Your 70’s run is a bona fide classic. I think the trade paperback collection of the Justin Hammer/”Demon In A Bottle” issues (THE POWER OF IRON MAN, collecting #120-#128) is not only the first TPB I remember seeing and owning, but the first collected edition I ever saw in a “real” bookstore. Don’t get me wrong, I loved the second run, but was there any trepidation on your part about going back to it? How’d it happen?

MICHELINIE: As I remember it, Mark Gruenwald was looking for new personnel to take over IRON MAN, and he called Bob and I individually to see if either of us would be interested. I assume that was because he’d liked our previous work on the book, but I guess it could have been because we were simply both available at the time. I’m sure there was some trepidation on my part, as I’d left the book years before because I felt I’d run out of Iron Man stories to tell. But I guess the time since then had allowed the idea well to fill up once more, and the thought of collaborating with Bob again sounded like fun, so I signed on. The collaboration process had changed by then; Bob and I had both grown creatively, Bob had done some writing on his own, and we were no longer living a few blocks away from each other in the same little college town, which meant that we had to plot over the phone instead of face-to-face. So the second run had something of a different tone to it, but I think we were still able to do some interesting stuff.

CASEY: An aspect of your work on AVENGERS and IRON MAN that really influenced much of my own work was the political aspect of those series. From Gyrich and the NSC dictating the Avengers’ membership to Tony Stark’s dealings with S.H.I.E.L.D., I don’t remember other comics from that time that dealt with even quasi-political material as it related to superheroes (aside from maybe Don McGregor). Were these things you were interested in exploring, or was its inclusion simply a function of the stories you wanted to tell?

MICHELINIE: I’ve never been a particularly political person. I have the normal and healthy mistrust of every politician that’s ever walked the face of the Earth, but other than that the subject doesn’t interest me that much. In the case of Henry Peter Gyrich in THE AVENGERS, I believe that was one of those things I inherited from Jim Shooter. I thought it was a great conflict, so I went with it. And with IRON MAN, it would have been difficult to NOT deal with politics. Tony Stark’s milieu was the world of global power; he was a major player in the realm of international commerce. And there’s no way he could have attained such a degree of success without learning to deal with the political ins and outs of both the United States and the foreign countries with which he dealt. Twisting that around, there’s not a politician alive who can get his/her job done without the cooperation of Big Business. So politics was simply a natural backdrop for stories growing out of that particular character.

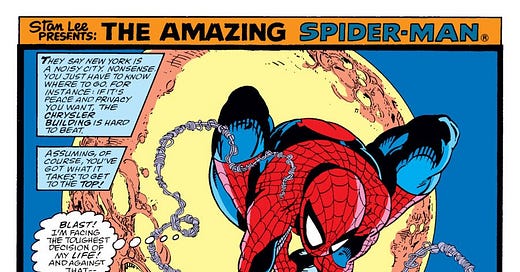

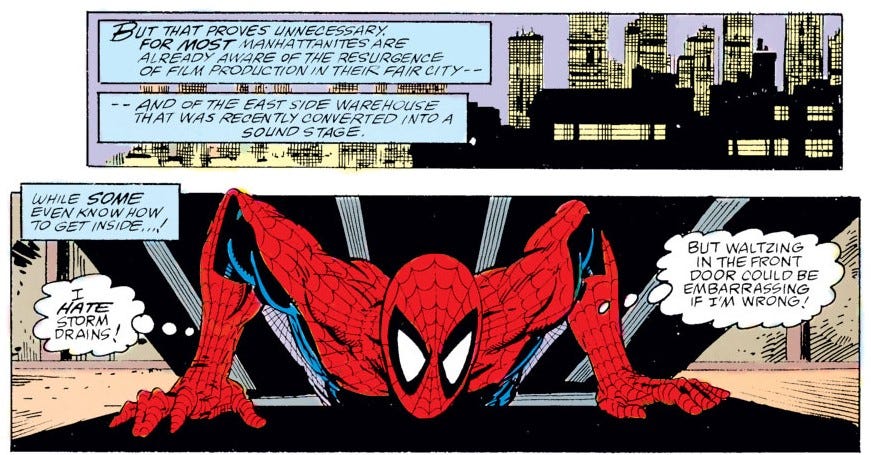

CASEY: I suppose this is a SPIDER-MAN-related question. To me, you’re one of the few writers of the 70’s and 80’s that was really able to update the Stan Lee-style of writing, that unique way of communicating with the reader while simultaneously providing a rip-roarin’ yarn. What is it about Stan’s writing that connected with you as a reader and how conscious were you of incorporating Stan-like elements into your own work…?

MICHELINIE: I didn’t consciously incorporate anyone’s elements into my Spider-Man stories. But Stan’s Spider-Man was what got me back into reading comics in college, after I’d “grown out” of them in junior high. I loved those stories, could relate to a central character who (and this may be a cliche now, but it’s sooooo true) had problems that I could identify with. So I’m sure I absorbed a lot of how Stan did things simply by reading his work over and over again, and that probably comes out in my writing to this day.

CASEY: Obviously, you were working with white-hot artists during your stint on AMAZING SPIDER-MAN. First, Todd McFarlane and then Erik Larsen. But I still say it was your voice that was the real, consistent treat of that run. Recently I really went back and read a good portion of your time on that series, and it was probably the most pure fun I’ve had reading superhero comics in years. I’m curious, though, what was it like to be at the epicenter of the pre-Image revolution. I mean, you were the last writer Todd and Erik worked with, which I think is significant. If the stories had sucked, I’m not sure they would’ve risen to the top of the heap in the manner they did. Do you feel like you gave those guys a platform to shine? And is that something that you considered with all of your artistic collaborators over the years…?

MICHELINIE: I truly believe that cream will rise to the top whether the milk is sweet or sour. I hope I provided interesting stories, and maybe the opportunity to draw some exciting visuals, but how well an artist deals with what they’re given depends on the amount of talent they bring to the table. I know my dialogue tends to be sharper when the pictures I’m working from are fun, and I imagine most artists put more into their pictures when they enjoy the plot they’re working from. I’ve been lucky to work with some fabulous artists throughout my career: Nestor Redondo, George Perez, Bob Layton, John Byrne, Walt Simonson, Dick Giordano and many, many more. Each of them brought their own quirks and creativity to the projects, and that brought out different elements of my own work. And that’s the bottom line: it’s the end product, the collaboration, that counts.

CASEY: Here’s a craft-based question: I’m assuming that you wrote a great deal of your work using the “Marvel method”. In other words, plot-first, after which you would dialogue the art after it was drawn. Did you ever write full script (during your time at DC, for example) and did you find yourself more comfortable with one method over the other…?

MICHELINIE: Actually, almost all of the stories I wrote for DC in my early years were written full script. That was the way I learned to write comics. I think I wrote maybe three or four “Marvel-style” scripts during that time to accommodate specific artists who preferred that process.

As such, I was definitely uncomfortable when I switched to the plot-pencils-script format at Marvel. It meant giving up a great deal of control over how the story was told. With full script, you can say exactly what goes on in every panel on every page; you’re at the wheel and can direct the whole show. But when you merely give an artist a plot, you’re leaving an awful lot of the storytelling to someone else. And artists, like writers, vary greatly in both their storytelling style and their ability to express story points clearly.

Once I got used to “Marvel-style,” however, I decided that while it might mean less control for the writer, it was probably the method that would produce the best end results. This is simply because the writer can see the pictures before he/she writes the words, giving the words and pictures a better chance of fitting together well. For instance: say you have a scene where a character is in the dark and stubs his toe. Writing full script, your total copy for that panel might be a word balloon saying, “Ow!”; you might think that’s all that’s necessary. But what if the artist draws a shadowy form in silhouette stumbling, simply saying, “Ow!” The reader’s going to wonder, “What happened? Did someone shoot him? Is there someone else in the room, did they hit him? Why’d he cry out?” But if you see that picture first, and realize that what’s going on isn’t clear, you can have the character think/say something like, “Ow! Damn chair leg! That toe’s gonna hurt for a month!” Thus letting the reader know what’s happened, and eliminating a possible hiccup in the flow of your story.

CASEY: Blunt question, but I’ve always been pretty curious about this. I hope it’s not too personal or too crass. Do you get any money from having created both Venom and Carnage? For Christ’s sake, Venom in particular went on to make boatloads of money for Marvel. Were there any character creation agreements in effect at the time?

MICHELINIE: I signed creator agreements for both Venom and Carnage, and I usually get a check once a year for any accumulated licensing shares. Marvel has been pretty good (as far as I know -- I haven’t checked their account books or anything) about sending money from action figures, T-shirts and such. But I did have to fight a long, frustrating battle to get anything from those characters’ appearances in video games, and I still haven’t received a single penny for Venom or Eddie Brock from any of the animated Spider-Man TV shows.

CASEY: I know THE BOZZ CHRONICLES holds a special place in your heart. Definitely an overlooked gem from the original Epic days. You own that series, right? Have you ever thought about taking it out for another spin? It seems to me that those kind of historical fantasy tales are certainly more in vogue these days…

MICHELINIE: Yep, I own Bozzy and his intrepid band. In fact, I recently had a lawyer look over my contract with Marvel to make sure, since I’d had a couple of nibbles from Hollywood about the series. And, yes, I have thought about doing more Bozz stories from time to time, but I don’t think I ever will. I’m really, really happy with that short run, and honestly don’t know if I could generate the same kind of stories today. I’m not necessarily speaking in terms of quality here, but those stories were written at a particular time in my life, when my viewpoint and experience were different than what they are today. Besides, I would be hard pressed to find an artist who could equal what Brett Blevins did, which is basically pluck images straight from my brain and draw them line-for-line on paper; I’ve rarely enjoyed such a perfect mating of talent and project. It just seems unlikely that I’d be able to duplicate the essence of that first run, at least to my own satisfaction.

CASEY: So, I’m proud to say that we share at least one thing in this business… we both had our stint writing Superman. Since I’m interviewing you, what did you take away from those years writing the Man of Steel…?

MICHELINIE: Uh... some pretty good paychecks? (Rimshot; cue laugh track.) But seriously, folks... I’ve been fortunate to write long runs of two cultural icons, Superman and Spider-Man. And to embrace a cliche, it doesn’t get much better than that. I was both delighted and surprised when Mike Carlin called and offered me ACTION COMICS, though I didn’t really realize what I was getting into. Being essentially one-fifth of a writer (writing one of four monthly books along with a quarterly, all fitting into a week-to-week continuity) certainly had its challenges. I usually ended up writing middle stories in the arcs, so I did a lot of treading water. It got frustrating on occasion, and going through three editors and three pencillers in three years meant constantly having to adjust, but it certainly wasn’t dull! Now if only I could write a Batman book to pull off the hat trick...

CASEY: Moving into novel-writing (which I know you’re currently concentrating on), have any specific skills you cultivated writing comicbooks ended up serving you in this medium or is simply 180 degrees away from anything comics-related?

MICHELINIE: For me, comics and prose are very different animals. I suppose the basics of storytelling are pretty much the same: a beginning, middle and end, character growth, conflict, climax, denouement, etc. But accomplishing those goals with words only, with no pictures to play off of, is quite a singular discipline. It’s like learning how to write all over again, particularly making sure the reader has all of the necessary information without giving something away, or becoming tediously detail-ridden. Right now the process for me is like pulling teeth with a pair of rusty pliers, but when I complete a chapter or story that I feel truly works, the satisfaction is immense.

About the only specific comic book skill that I’ve found to be helpful on a regular basis is plotting ahead. I’m used to working out a full plot (so the artist can draw it) before writing a comics story, and I’ve found that works well for me with prose short stories. I always have a fairly detailed outline either in mind or in note form before sitting down to actually write the story. But I haven’t made that work for novels yet; I’m just too impatient to spend days or weeks working out all of the specifics of a 300-page book. I tend to sit at the computer and just start banging away. As a result, I frequently end up with a chapter or two and then just sit there wondering, “Okay, what now?” Oh, well, maybe I can sell those dangling chapters as collectables on eBay...

If you’re not already familiar with David’s work, just head over to Amazon.com and simply do a search on his name. You’ll be shocked at how much of his work has been collected over the years. And it’s all great fun. Trust me, you won’t regret a single purchase.

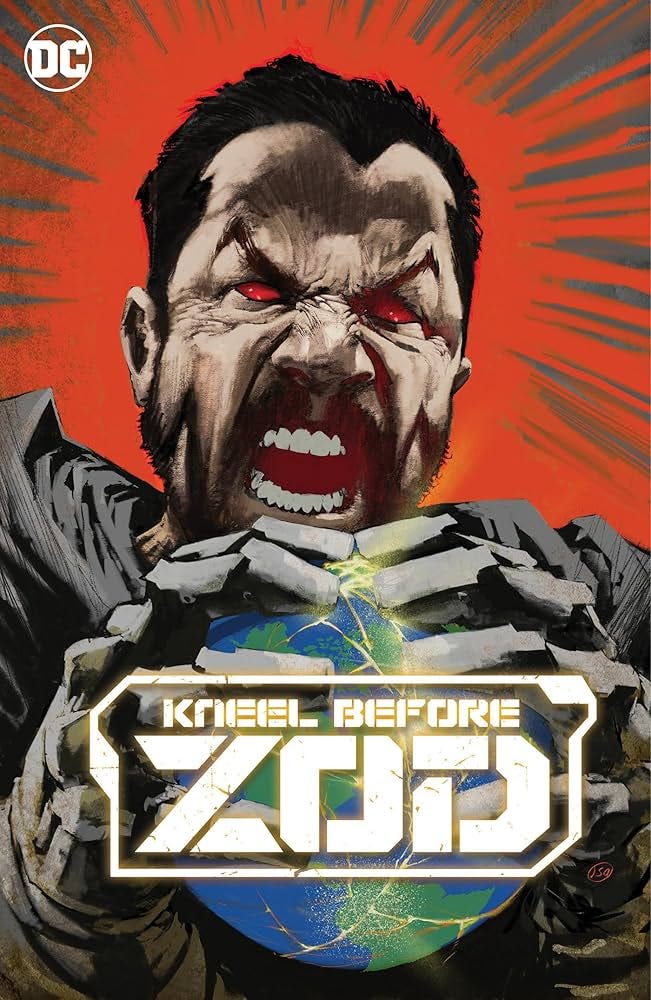

ON SALE NOW: I referenced it in the last newsletter, and lo and behold, the trade paperback collection of the KNEEL BEFORE ZOD series I wrote for DC Comics last year is in stores this week. Starring Superman’s best pal, General Zod, there’s some pretty good shit in this thing, and artist Dan McDaid practically killed himself on it. Check it out.

Joe Casey

USA

I loved the Newsarama of yore. And this interview was great.

Amazing interview! Michelinie comics were a staple of my youth.

Very prescient question in regards to Venom/Carnage - I hope he gets some royalties from the Venom movies..! (and Scott Lang, and Taskmaster, Ghost, etc)