END OF THE LINE?

Where we find ourselves (Part One of Two)

Buckle up, folks. I’m in a bit of a mood… and I’m about to seriously go off…

… well, maybe.

This is a very weird place that we’ve finally found ourselves. And when I say “we”… I’m talking about all of us who have grown up in the very specific arena of the comicbook industry’s so-called “mainstream”… all of us who have stood hand-in-hand with our local comicbook stores and the retailers who own/run them… all of us who have come of age in the constant shadow of the “Big Two”.

Ah, yes. The Big Two. Also known as Marvel and DC. The thing is… as publishers of superhero comicbooks, they just don’t seem to cast quite the same shadow as they used to, and with each successive generation, that shadow seems to diminish more and more. That means there are less of “us” than there used to be.

But that’s the point.

Our industry is not at its strongest right now. And not even close to being at its healthiest.

And don’t talk to me about sales figures. Don’t come back at me with a bullshit argument about how certain comicbooks are selling 300K or 400K in the Direct Market right now. That’s all well and good, but I’m just not that interested in sales figures that have been goosed by variant covers and order incentives, publisher-initiated schemes that are meant to engender short-term gains over the long-term health of the industry. Obviously, it’s an accomplishment of commerce and it’s perfectly legitimate for certain industry circles to celebrate that. The Big Two are corporate entities and the primary function of a corporation is to make money. And to make as much of it as humanly possible. So, y’know, yay for money! Blah, blah, blah…

No, I’m not talking about sales here. I’m talking about readers. And I just don’t think we have very many of those right now.

I have a few theories about why that is and, for the purposes of this newsletter (which, I should remind everyone, is free for one and all), I’m going to present as fact. Since the early 1960’s (and probably before, to a certain extent), the mainstream comicbook industry has relied on new generations to keep it not just healthy, but thriving.

And that goes for professionals, too. In fact, let’s talk about them (me) first. There’s a definite generational thing that applies to comicbook professionals that -- if you look at the history of the industry -- is tough to deny (not that anybody is denying it, but no one seems to ever talk about it. Not in this context, at least). Trust me, it’ll all come back to why there’s a lack of readers (eventually).

The first generation of creators -- the ones that ushered in the so-called Silver Age --were mostly holdovers from the end of the Golden Age, writers and artists and other craftsmen in their late 30’s/early 40’s (which, in those years, was considered middle aged) that had somehow managed to hang on through the lean years of the 1950’s and were still around to draft the new superhero stories pioneered by DC Comics with Showcase #4 in 1956 but soon usurped by the Marvel Age of Comics, beginning with Fantastic Four #1 in 1961. Basically, the Mad Man generation was making comicbooks (if anyone remembers that TV series from a decade and a half ago).

These creators were not fans per se. They were simply the men and women doing their jobs to the best of their abilities, delivering periodical entertainment -- for an accepted audience of mostly prepubescent readers. And we salute them for it.

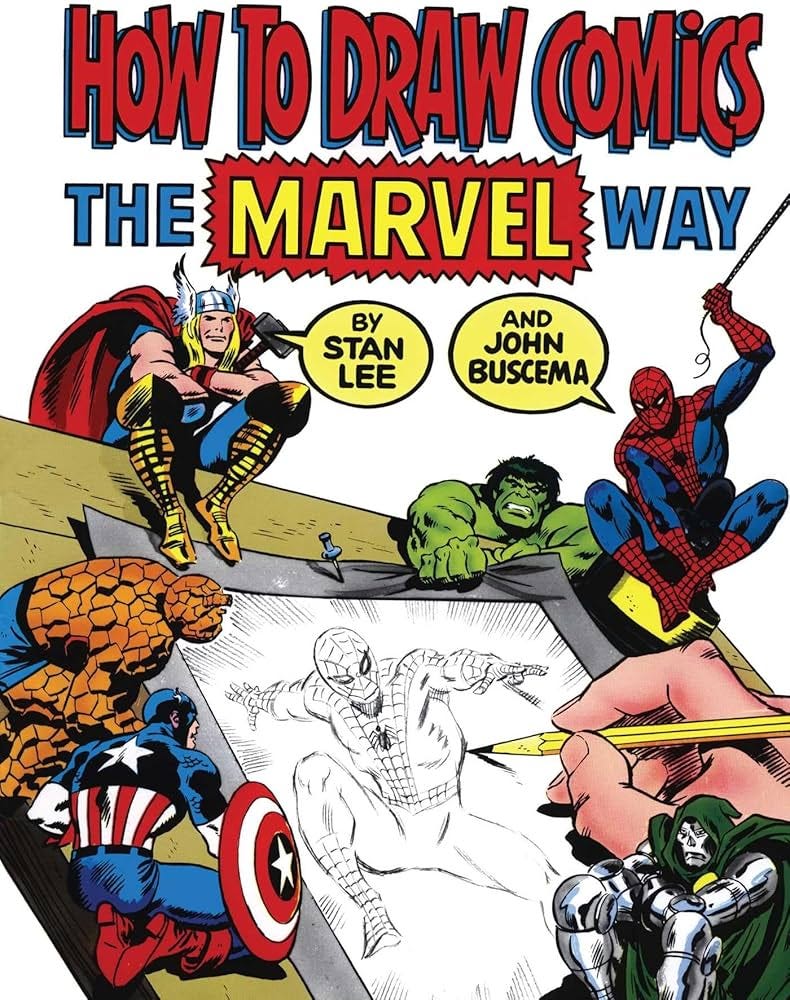

Stan Lee, in particular, was raising the bar significantly in his comicbooks with his newfound writing style (effectively transforming himself into the omniscient voice of Marvel Comics). But, despite whatever pretensions he might’ve held at the time, he knew he was still talking to kids. At first, anyway.

Then came Stan Lee’s first protégé and heir apparent, Roy Thomas, in the mid-1960’s. As an outright devotee of the Golden Age comicbooks that he grew up reading, Thomas’ passion practically defined his entire creative life. When he wasn’t actively bringing back Golden Age continuity and fusing it to 1960’s/1970’s Marvel continuity, he was bending over backwards to make the modern comicbooks he was writing -- most notably, the Avengers monthly series -- more closely echo the superhero comicbooks of his youth. Sure, he was still writing comicbooks for kids, but he was also writing them for himself.

The second wave of creators that followed Thomas -- the ones that pretty much initiated (and defined) the Bronze Age -- started breaking into the business in significant numbers in the late 1960’s/early 1970’s. These were creators that had been reading the comicbooks of the Silver Age and were eager to join in the fun. Sure, they were fans, but only to a certain degree. They wanted to actively contribute to the continuities they had been reading. But things were still a bit nebulous, in terms of focus. These creators would vacillate freely between making traditional superhero comicbooks… and really pushing the envelope. These guys had some genuine artistic aspirations and they were often out to please themselves. I’m talking about creators like Jim Steranko, Neal Adams, Steve Englehart, Steve Gerber, Frank Brunner, Jim Starlin and Bernie Wrightson, to name just a few. Blame it on the drugs, if you’d like. But you can definitely see it in the comicbooks they were making.*

*A quick aside for the anal retentive out there: of course I’m not discounting the numerous outside influences each creator brought to their work. Whether drawing from literature, music or cinema, these creators each had their own, individual interests -- and personal eccentricities -- that obviously informed their work. So, yeah, this kooky theory of mine isn’t completely myopic in its focus, okay…?

The third wave of creators that broke in during the mid- to late-1970’s were, in fact, the true “second generation” of comicbook professionals that not only grew up on the comicbooks of the Silver Age -- particularly the Marvel Comics of the 1960’s -- they often sprang straight out of organized fandom. These folks were eager to get their hands on the characters that made such a strong impression on them when they were very young. But, because of the sheer power of that impression, they entered the industry not only inspired by the comicbooks they had loved as kids… but they set out to, in a sense, recreate them in their own work. Which is exactly what they did when they finally came to the forefront as creators in the early 1980’s. Most of these folks were not only writer/artists, but they were also more traditionalist in nature, more inclined to try and recapture the feeling in their own work they’d had in their adolescence, reading Lee and Kirby and Ditko and the rest in those early Marvels. They were less interested in pushing the envelope. That’s where you get John Byrne writing and drawing Fantastic Four as a carefully crafted echo of the original Lee/Kirby run… George Pérez drawing Avengers like Kirby crossed with John Buscema… Walt Simonson writing/drawing Thor in the cosmic Kirby tradition… Frank Miller writing/drawing Daredevil like a Gil Kane/Will Eisner hybrid… and so on.

At that point, the mainstream was fully onboard the nostalgia train, with each successive generation striving to recreate/restore the comicbooks of their youth -- while occasionally adding a dash of their own creative vision. They’d learned from previous generations, so that meant not so much creative vision as to rock the corporate boat, but just enough to push the envelope ever so slightly (and, in a more self-serving way, individualize and brand their work). Nevertheless, the cycle of feedback loops -- or, more specifically, the “influence loops” -- had begun. While Alan Moore’s impact on comicbooks in the Eighties as a singular voice is undeniable, it doesn’t take too much investigation to see that Moore was, in fact, a synthesis of specific influences being published ten years before he was employed by DC, specifically the late 1960’s/early 1970’s underground comix and the purple prose of mid-1970’s Marvel writers like Don McGregor, Steve Gerber and Doug Moench. When he went on to write a handful of Superman stories in the mid-1980’s, and especially his run on Rob Liefeld’s Supreme in the 1990’s, Moore was specifically recreating the Silver Age Superman comicbooks he’d read as a kid. I mean, he flat out admitted to it in interviews. He would eventually go all-in on this approach with his America’s Best Comics imprint (published by DC/Wildstorm) in the early 2000’s

When nobody was looking too closely, the Nostalgia Comic practically became its own genre.

And on it went. As comicbook professionals became even more historically literate, more self-reflective and insightful in their outlooks, and more press-savvy… these trends were more openly exposed and discussed. My fellow X-writer and comicbook raconteur supreme, the much-smarter-than-me Grant Morrison, used to talk at length about how Iain Spence’s theory of cultural cycles (also known as the Sekhmet Hypothesis) could be used to track -- and, in some ways, predict -- the evolutionary changes we’ve all seen throughout the various “ages” of superhero comicbooks by paying close attention to, of all things, sunspot cycles. It’s heady stuff and good fun to try and wrap your brain around.

And while I hate to disagree with my friend of more than a quarter century… it wasn’t simply cyclical. It was, in fact, generational. Personally, I just think it has less to do with sunspots and more to do with 1) when you were born and 2) what comicbooks you were reading and absorbing in the years before you turned professional.

By the way, I’m as guilty of this behavior as anyone I’m mentioning here. I’ve certainly done my fair share of Nostalgia Comics over the last twenty-five years, right up until this year. So, yeah, I know what I’m talking about…!

Now consider the “greatest hits” approach to mainstream comicbooks that became popular about a quarter century ago. It really began in earnest with Marvel’s Heroes Return books in the late 1990’s -- in terms of having genuine sales impact -- but gained real steam after the turn of the millennium with Grant Morrison’s New X-Men, the original Batman: Hush, Wildstorm’s Planetary series and, to an extent, the first batch of Marvel’s Ultimate line, all of which did a lot to lure back an aging generation of readers that might’ve otherwise grown out of superhero comicbooks completely. And, because of that, it set a template that other books and creators continued throughout the remainder of the decade. It was, in fact, the height of Nostalgia Comics.

Another random observation: With their extended run on Batman, almost twenty years ago now, Grant Morrison even went one step further, effectively creating the Interactive Nostalgia Comic. But maybe that’s a topic for another newsletter…

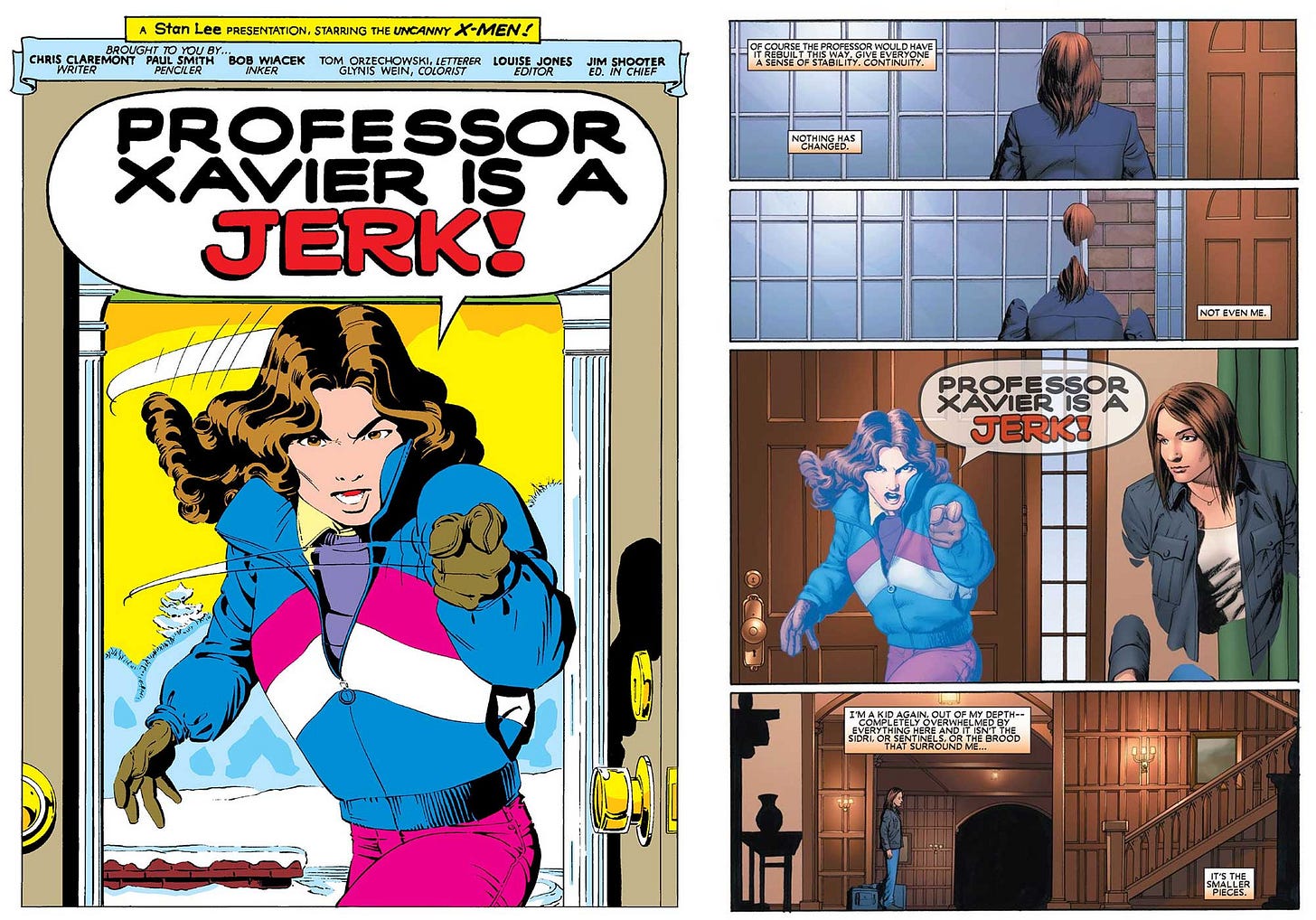

So, anyway… imagine a current writer at Marvel or DC -- let’s assume relatively young in age, like late 20’s-to-mid 30’s -- that was actually reading comicbooks in their pre-teen years (and beyond) and being influenced by them (as my generation was by the comicbooks we read when we were kids). So what were they reading then? Comicbooks circa 2004, maybe? Right smack in the middle of the prime era of Nostalgia Comics. If they were reading X-Men at all, they weren’t reading the classic Claremont/Byrne/Cockrum/Smith Uncanny X-Men -- some of the most cutting edge mainstream superhero comicbooks of their day —they were most likely reading a flat-out love letter to that era, the Whedon/Cassaday Astonishing X-Men (which, while brilliantly executed, brought nothing substantially new to the party aside from a glorious recapitulation of the comicbooks that those creators had grown up on). So, okay, when that writer grows up, breaks in and ends up writing the X-Men, for example, what are they drawing on as their foundational knowledge of the IP? I might be curious… hat manner of Nostalgia Comics -- if any -- are we going to see from them?

(again, there are obviously exceptions… there are certainly those younger writers working now who were/are dedicated students of the medium, and have read the classics in back issues and can cite them as bona fide influences. But like I always say… it’s the exceptions that tend to prove the rule)

Now, before you can start accusing me of being entirely writer-centric… this whole crazy theory applies to artists, as well, but with a couple of subtle differences. For one thing, with artists, we’re talking about visual styles as opposed to narrative story content. And even more interesting, from the second generation on, artists tended to break in at a much younger age than their writer peers, which put them that much closer to their primary influences. Rich Buckler followed closely in Jack Kirby’s stylistic footsteps when he started at Marvel in the early 1970’s. Barry Windsor Smith was practically a Kirby clone when he broke in a few years prior. Same with Keith Giffen a few years later. John Byrne was drawing Uncanny X-Men in a refined style that heavily echoed one of his artistic heroes, Neal Adams, who’s own influential run on X-Men was only a few years old when Byrne had broken in. Rob Liefeld was obviously inspired by the Marvel artists of the 1970’s like Pérez and Byrne, but his actual, on-the-page artistic chops were more directly influenced by more recent artists (to him) like Michael Golden and Art Adams. Adams, in particular, only pre-dates Rob’s entry into the business by a mere four years (if that). The great Phil Jimenez broke in during the early 1990’s emulating George Pérez to an almost ridiculous degree, his major influence being Pérez’s seminal Wonder Woman run (who’s artwork on that run wrapped up just a couple of years previously). So, as you can see, the “influence loops” for artists could be even tighter. And often even more obvious.

Okay, shit… I may be actively skidding off the rails here. I mean, I’m all over the place. Hey, it happens. In the next newsletter we’ll finally get around to the readers, how my crackpot theories relate to them... and how it’s put us, as an industry, in some dire straits indeed. Which is really what this entire ridiculous rant is all about.

In the meantime -- and I need to start mentioning this more often -- feel free to sound off in the comments section. Share your differing opinions or your seething outrage. Let’s start mixing it up. In the sage words of Tangina Barrons, “All are welcome!”

Joe Casey

USA

There are two distinct purchasers of comics.

Readers & Collectors.

Too many people want to send off 32 pages of creation and get it put into an encasement where they can look at a cover and an advert on the back.

Too few want to experience the wonder you can get from a page turn.

I want to get that serialised wonder.

I want the writer and artist to hit me with emotion.

Give me a rollercoaster with paper and ink.

I don't give a flying fig about a bit of plastic with a 9.8 label.

I was a huge fan of Starman, which is one of the best nostalgia comics of its' day. Following James Robinson led me to your work. I personally love the nostalgia genre, as you call it.

I think the real issue with gaining newer, younger readers is the "competition" with Manga. Manga is comics, right? I'm not sure how to say what I'm thinking, there. Perhaps that is a different conversation.

I have a 29 year old daughter. She reads comics. She loves Starman, too, BTW. But she does not buy the monthly books. She reads graphic novels. And she prefers small press books to anything from Marvel or DC.